Paul Mawhinney, a former music-store owner in Pittsburgh, spent more than 40 years amassing a collection of some three million LPs and 45s, many of them bargain-bin rejects that had been thoroughly forgotten. The world’s indifference, he believed, made even the most neglected records precious: music that hadn’t been transferred to digital files would vanish forever unless someone bought his collection and preserved it.

Mawhinney spent about two decades trying to find someone who agreed. He struck a deal for $28.5 million in the late 1990s with the Internet retailer CDNow, he says, but the sale of his collection fell through when the dot-com bubble started to quiver. He contacted the Library of Congress, but negotiations fizzled. In 2008 he auctioned the collection on eBay for $3,002,150, but the winning bidder turned out to be an unsuspecting Irishman who said his account had been hacked.

Then last year, a friend of Mawhinney’s pointed him toward a classified ad in the back of Billboard magazine:

RECORD COLLECTIONS. We BUY any record collection. Any style of music. We pay HIGHER prices than anyone else.

That fall, eight empty semitrailers, each 53 feet long, arrived outside Mawhinney’s warehouse in Pittsburgh. The convoy left, heavy with vinyl. Mawhinney never met the buyer.

“I don’t know a thing about him — nothing,” Mawhinney told me. “I just know all the records were shipped to Brazil.”

Just weeks before, Murray Gershenz, one of the most celebrated collectors on the West Coast and owner of the Music Man Murray record store in Los Angeles, died at 91. For years, he, too, had been shopping his collection around, hoping it might end up in a museum or a public library. “That hasn’t worked out,” The Los Angeles Times reported in 2010, “so his next stop could be the Dumpster.” But in his final months, Gershenz agreed to sell his entire collection to an anonymous buyer. “A man came in with money, enough money,” his son, Irving, told The New York Times. “And it seemed like he was going to give it a good home.”

Those records, too, were shipped to Brazil. So were the inventories of several iconic music stores, including Colony Records, that glorious mess of LP bins and sheet-music racks that was a Times Square landmark for 64 years. The store closed its doors for good in the fall of 2012, but every single record left in the building — about 200,000 in all — ended up with a single collector, a man driven to get his hands on all the records in the world.

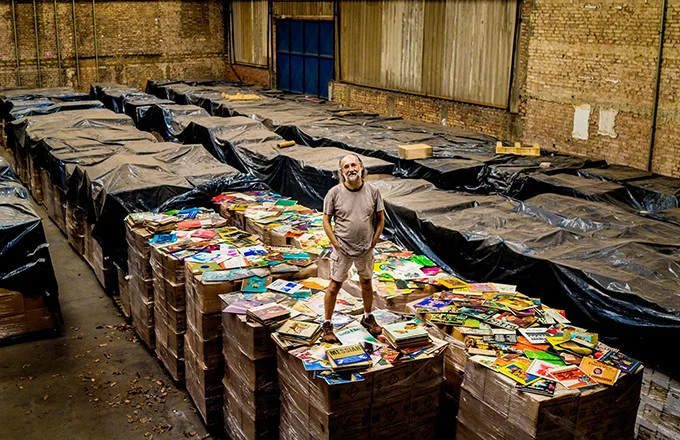

In an office near the back of his 25,000-square-foot warehouse in São Paulo, Zero Freitas, 62, slipped into a chair, grabbed one of the LPs stacked on a table and examined its track list. He wore wire-rimmed glasses, khaki shorts and a Hard Rock Cafe T-shirt; his gray hair was thin on top but curled along his collar in the back. Studying the song list, he appeared vaguely professorial. In truth, Freitas is a wealthy businessman who, since he was a child, has been unable to stop buying records. “I’ve gone to therapy for 40 years to try to explain this to myself,” he said.

Continue reading the main story

His compulsion to buy records, he says, is tied up in childhood memories: a hi-fi stereo his father bought when Freitas was 5 and the 200 albums the seller threw in as part of the deal. Freitas was an adolescent in December 1964 when he bought his first record, a new release: “Roberto Carlos Sings to the Children,” by a singer who would go on to become one of Brazil’s most popular recording stars. By the time he finished high school, Freitas owned roughly 3,000 records.

After studying music composition in college, he took over the family business, a private bus line that serves the São Paulo suburbs. By age 30, he had about 30,000 records. About 10 years later, his bus company expanded, making him rich. Not long after that, he split up with his wife, and the pace of his buying exploded. “Maybe it’s because I was alone,” Freitas said. “I don’t know.” He soon had a collection in the six figures; his best guess at a current total is several million albums.

Recently, Freitas hired a dozen college interns to help him bring some logic to his obsession. In the warehouse office, seven of them were busy at individual workstations; one reached into a crate of LPs marked “PW #1,425” and fished out a record. She removed the disc from its sleeve and cleaned the vinyl with a soft cloth before handing the album to the young man next to her. He ducked into a black-curtained booth and snapped a picture of the cover. Eventually the record made its way through the assembly line of interns, and its information was logged into a computer database. An intern typed the name of the artist (the Animals), the title (“Animalism”), year of release (1966), record label (MGM) and — referencing the tag on the crate the record was pulled from — noted that it once belonged to Paulette Weiss, a New York music critic whose collection of 4,000 albums Freitas recently purchased.

The interns can collectively catalog about 500 records per day — a Sisyphean rate, as it happens, because Freitas has been burying them with new acquisitions. Between June and November of last year, more than a dozen 40-foot-long shipping containers arrived, each holding more than 100,000 newly purchased records. Though the warehouse was originally the home of his second business — a company that provides sound and lighting systems for rock concerts and other big events — these days the sound boards and light booms are far outnumbered by the vinyl.

Many of the records come from a team of international scouts Freitas employs to negotiate his deals. They’re scattered across the globe — New York, Mexico City, South Africa, Nigeria, Cairo. The brassy jazz the interns were listening to on the office turntable was from his man in Havana, who so far has shipped him about 100,000 Cuban albums — close to everything ever recorded there, Freitas estimated. He and the interns joke that the island is rising in the Caribbean because of all the weight Freitas has hauled away.

Allan Bastos, who for years has served as Freitas’s New York buyer, was visiting São Paulo and joined us that afternoon in the warehouse office. Bastos, a Brazilian who studied business at the University of Michigan, used to collect records himself, often posting them for sale on eBay. In 2006, he noticed that a single buyer — Freitas — was snapping up virtually every record he listed. He has been buying records for him ever since, focusing on U.S. collections. He has purchased stockpiles from aging record executives and retired music critics, as well as from the occasional celebrity (he bought the record collection of Bob Hope from his daughter about 10 years after Hope died). This summer Bastos moved to Paris, where he’ll buy European records for Freitas.

Continue reading the main story

Bastos looked over the shoulder of an intern, who was entering the information from another album into the computer.

“This will take years and years,” Bastos said of the cataloging effort. “Probably 20 years, I guess.”

Twenty years — if Freitas stops buying records.

Collecting has always been a solitary pursuit for Freitas, and one he keeps to himself. When he bought the remaining stock of the legendary Modern Sound record store in Rio de Janeiro a couple of years ago, a Brazilian newspaper reported that the buyer was a Japanese collector — an identity Bastos invented to protect Freitas’s anonymity. His collection hasn’t been publicized, even within Brazil. Few of his fellow vinyl enthusiasts are aware of the extent of his holdings, partly because Freitas never listed any of his records for sale.

But in 2012, Bob George, a music archivist in New York, traveled with Bastos to São Paulo to prepare for Brazilian World Music Day, a celebration that George organized, and together they visited Freitas’s home and warehouse; the breadth of the collection astonished George. He was reminded of William Randolph Hearst, the newspaper magnate who lusted after seemingly every piece of art on the world market and then kept expanding his private castle to house all of it.

“What’s the good of having it,” George remembers telling Freitas, “if you can’t do something with it or share it?”

The question nagged at Freitas. For the truly compulsive hobbyist, there comes a time when a collection gathers weight — metaphysical, existential weight. It becomes as much a source of anxiety as of joy. Freitas in recent years had become increasingly attracted to mystic traditions — Jewish, Christian, Hindu, Buddhist. In his house, he and his second wife created a meditation room, and they began taking spiritual vacations to India and Egypt. But the teachings he admired didn’t always jibe with his life as a collector — acquiring, possessing, never letting go. Every new record he bought seemed to whisper in his ear: What, ultimately, do you want to do with all this stuff?

He found a possible model in George, who in 1985 converted his private collection of some 47,000 records into a publicly accessible resource called the ARChive of Contemporary Music. That collection has grown to include roughly 2.2 million tapes, records and compact discs. Musicologists, record companies and filmmakers regularly consult the nonprofit archive seeking hard-to-find songs. In 2009 George entered into a partnership with Columbia University, and his archive has attracted support from many musicians, who donate recordings, money or both. The Rolling Stones guitarist Keith Richards has provided funding for the archive’s collection of early blues recordings. David Bowie, Paul Simon, Nile Rodgers, Martin Scorsese and Jonathan Demme all sit on its board.

Freitas has recently begun preparing his warehouse for his own venture, which he has dubbed Emporium Musical. Last year, he got federal authorization to import used records — an activity that hadn’t been explicitly allowed by Brazilian trade officials until now. Once the archive is registered as a nonprofit, Freitas will shift his collection over to the Emporium. Eventually he envisions it as a sort of library, with listening stations set up among the thousands of shelves. If he has duplicate copies of records, patrons will be able to check out copies to take home.

Continue reading the main story

Some of those records are highly valuable. In Freitas’s living room, a coffee table was covered with recently acquired rarities. On top of a stack of 45s sat “Barbie,” a 1962 single by Kenny and the Cadets, a short-lived group featuring the Beach Boys’ Brian Wilson on lead vocals and, as backup singers, Wilson’s brother Carl and their mother, Audree. In the same stack was another single — “Heartache Souvenirs"/"Chicken Shack,” by William Powell — that has fetched as much as $5,000 on eBay. Nearby sat a Cuban album by Ivette Hernandez, a pianist who left Cuba after Fidel Castro took power; Hernandez’s likeness on the cover was emblazoned with a bold black stamp that read, in Spanish, “Traitor to the Cuban Revolution.”

While Freitas thumbed through those records, Bastos was warning of a future in which some music might disappear unnoticed. Most of the American and British records Freitas has collected have already been digitally preserved. But in countries like Brazil, Cuba and Nigeria, Bastos estimated, up to 80 percent of recorded music from the mid-20th century has never been transferred. In many places, he said, vinyl is it, and it’s increasingly hard to find. Freitas slumped, then covered his face with his hands and emitted a low, rumbling groan. “It’s very important to save this,” he said. “Very important.”

Freitas is negotiating a deal to purchase and digitize thousands of Brazilian 78 r.p.m. recordings, many of which date to the early 1900s, and he expects to digitize some of the rarest records in his collection shortly thereafter. But he said he could more effectively save the music by protecting the existing vinyl originals in a secure, fireproof facility. “Vinyl is very durable,” he said. “If you store them vertically, out of the sun, in a temperature-controlled environment, they can pretty much last forever. They aren’t like compact discs, which are actually very fragile.”

In his quest to save obscure music, Bastos told me, Freitas sometimes buys records he doesn’t realize he already owns. This spring he finally acquiesced to Bastos’s pleas to sell some of his duplicate records, which make up as much as 30 percent of his total collection, online.

“I said, ‘Come on, you have 10 copies of the same album — let’s sell four or five!’ ” Bastos said.

Freitas smiled and shrugged. “Yes, but all of those 10 copies are different,” he countered. Then he chuckled, as if recognizing how illogical his position might sound.

In March, he began boxing up 10,000 copies of Brazilian LPs to send to George in an exchange between the emerging public archive and its inspirational model. It was a modest first step, but significant. Freitas had begun to let go.

Earlier this year, Freitas and Bastos stopped into Eric Discos, a used-record store in São Paulo that Freitas frequents. “I put some things aside for you,” the owner, Eric Crauford, told him. The men walked next door, where Crauford lives. Hundreds of records and dozens of CDs teetered in precarious stacks — jazz, heavy metal, pop, easy listening — all for Freitas.

Continue reading the main story Continue reading the main story

Sometimes Freitas seems ashamed of his own eclecticism. “A real collector,” he told me, is someone who targets specific records, or sticks to a particular genre. But Freitas hates to filter his purchases. Bastos once stumbled upon an appealing collection that came with 15,000 polka albums. He called Freitas to see if it was a deal breaker. “Zero was asking me about specific polka artists, whether they were in the collection or not,” Bastos remembered. “He has this amazing knowledge of every kind of music.”

That afternoon, Freitas purchased Crauford’s selections without inspecting them, as he always does. He told Crauford he’d send someone later in the week to pick them up and deliver them to his house. Bastos listened to the exchange without comment but noted the destination of the records — Freitas’s residence, not the archive’s warehouse. He was worried that the collector’s compulsions might be getting in the way of the archiving efforts. “Zero isn’t taking too many of the records to his house, is he?” Bastos had asked a woman who helps Freitas manage his cataloging operation.

No, she told him. But almost every time Freitas picked up a record at the archive, he’d tell a whole story about it. Often, she said, he’d become overwhelmed with emotion. “It’s like he almost cries with every record he sees,” she told him.

Freitas’s desire to own all the music in the world is clearly tangled up in something that, even after all these years, remains tender and raw. Maybe it’s the nostalgia triggered by the songs on that first Roberto Carlos album he bought, or perhaps it stretches back to the 200 albums his parents kept when he was small — a microcollection that was damaged in a flood long ago but that, as an adult, he painstakingly recreated, album by album.

After the trip to Eric Discos, I descended into Freitas’s basement, where he keeps a few thousand cherry-picked records, a private stash he doesn’t share with the archive. Aside from a little area reserved for a half-assembled drum kit, a couple of guitars, keyboards and amps, the room was a labyrinth of floor-to-ceiling shelving units filled with records.

He walked deep into an aisle in search of the first LP he ever bought, the 1964 Roberto Carlos record. He pulled it from the shelf, turning it slowly in his hands, staring at the cover as if it were an irreplaceable artifact — as if he did not, in fact, own 1,793 additional copies of albums by Roberto Carlos, the artist who always has, and always will, occupy more space in his collection than anyone else.

Nearby sat a box of records he hadn’t shelved yet. They came from the collection of a man named Paulo Santos, a Brazilian jazz critic and D.J. who lived in Washington during the 1950s and who was friendly with some of the giants of jazz and modern classical music. Freitas thumbed through one album after another — Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Leonard Bernstein, Dave Brubeck. The records were signed, and not with simple autographs; the artists had written affectionate messages to Santos, a man they obviously respected.

“These dedications are so personal,” Freitas said, almost whispering.

He held the Ellington record for an extended moment, reading the inscription, then scanning the liner notes. Behind his glasses, his eyes looked slightly red and watery, as if something was irritating them. Dust, maybe. But the record was perfectly clean.