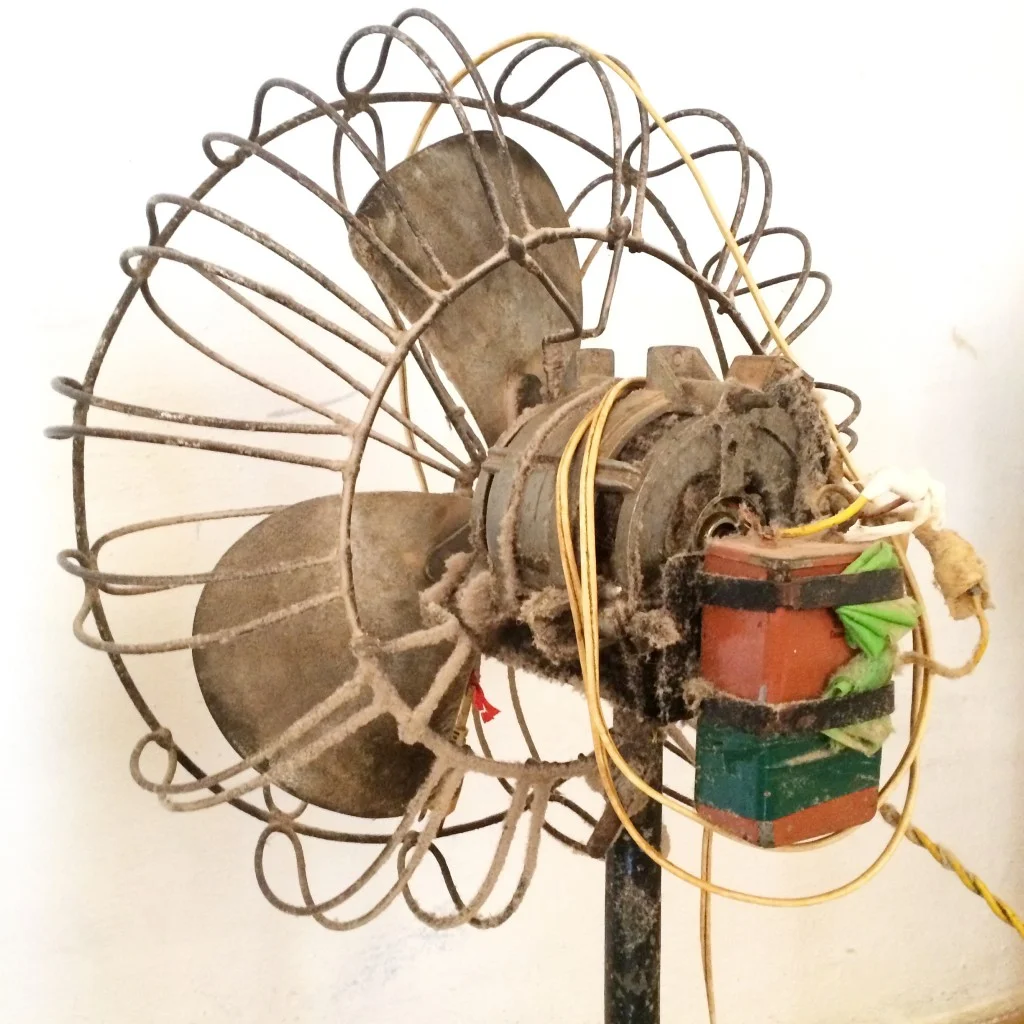

Just outside Havana, in the childhood bedroom of illustrator Edel Rodriguez, a washing machine engine welded to a boat propeller has become a makeshift fan. This kind of cobbled-together contraption is common in Cuba. So are stoves that run on diesel from trucks, satellite dishes made of garbage can lids and lunch trays, and taxi signs consisting of old fuel canisters.

Cubans are masters of invention. They have to be. In 1960, President Dwight D. Eisenhower slapped the first trade embargo on the country, and in 1961, just before leaving office, he broke off diplomatic relations. After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the loss of oil imports, shortages got worse. The country lost about 80 percent of its imports, and the economy shrank by 34 percent.

So Cubans learned to make do. When something breaks, they patch it up. When something doesn’t work, they fix it. And when something is altogether lost, they invent it. They grill meat on metal chairs. They seal the bottoms of cars, transforming them into boats. From the suffering of 30 years of isolation has sprung a generation of amateur engineers, inventors and welders.

“A market started with people who can rig things up,” said Rodriguez, who was born and raised in the small Cuban farm town, El Gabriel. In 1980, at age 9, he fled to Miami with his family on the Mariel boatlift, and he now lives in New Jersey. “It’s what Cubans have been in the last 60 years – just really inventive with things.”

Ernesto Oroza, a Cuban-born designer who now lives in Miami, said several factors played a role in the DIY phenomenon. A high percentage of Cubans had engineering degrees, thanks to a system of free education. Many became intimately familiar with the mechanics of the standardized socialist products found in most homes — the Soviet-designed Aurika washing machine, for example, and the Orbita fan. Plus, no one was untouched by the crisis.

“Musicians, medical doctors, workers, homemakers, athletes and architects all had to dedicate themselves to making their own things and meeting the emerging needs of the family,” Oroza wrote over email in Spanish. “The Cuban home became a laboratory for inventions and survival.”

Oroza, who has spent decades collecting, studying and writing about these objects, has a name for the phenomenon: “technological disobedience.” Cubans, he said, weren’t deterred by complexity or scale, and they learned to disrespect the “authority” of objects. That meant rethinking their original purpose and life cycle.

People scoured the city for plastic objects and industrial discards and swiped garbage from city dumpsters, which they’d grind up and inject into molds to make toys, dishes, electrical switches and footwear. The magazine Popular Mechanics was a hot commodity on the island.

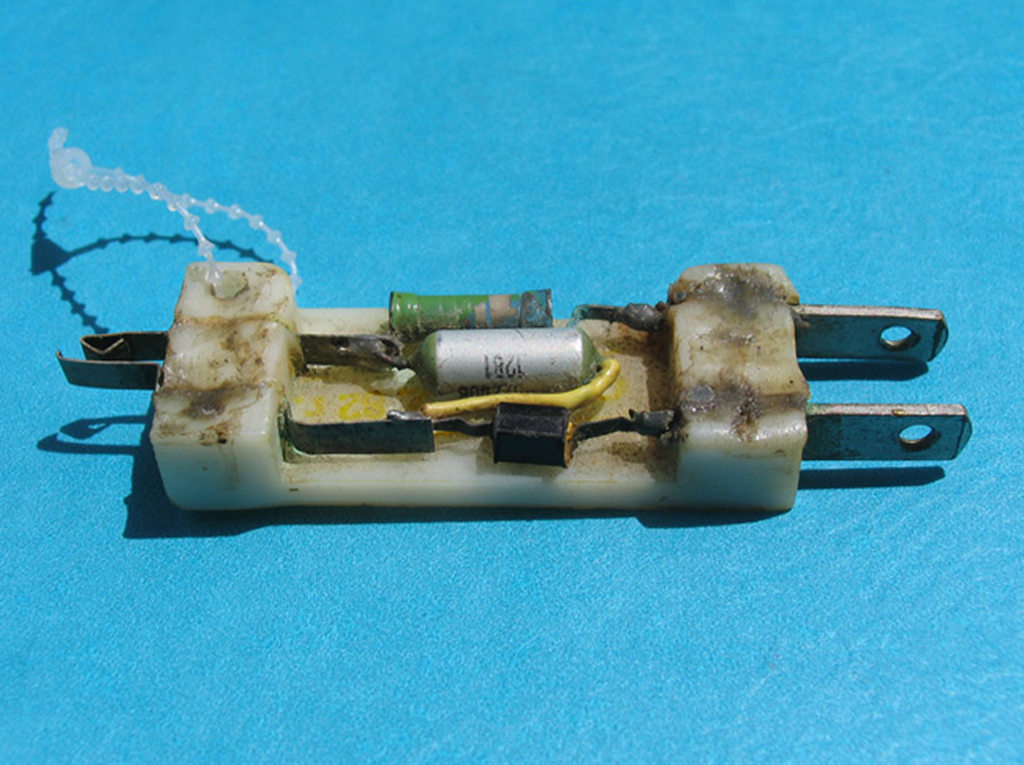

“Industrial products were tinkered with and examined by hand,” Oroza said. “Cubans dissected the industrial culture, opening everything up, repairing and altering every type of object.”

Washing machine motors were especially sought after. With the warm weather in Cuba, people could do without the dryers. So they found other uses. These motors powered fans, lawnmowers, shoe repair tools and key copiers.

They were used to chop vegetables and, below, to shred coconut.

In 1992, The Cuban military issued a book called “Con Nuestros Propios Esfuerzos” (With Our Own Efforts) that detailed crowdsourced ideas on manipulating, repairing or reusing everyday objects. Among them was a recipe to turn grapefruit rind into a “steak” by marinating it with lemon juice, onion and garlic and frying it up on a pan.

With rations so scarce, much of the average Cuban day is spent hunting for the basics, said Rodriguez, who has returned several times since he left to visit family in Cuba.

“You get up at 7 in the morning, and say, ‘Where is there bread? Where do you get milk? Do you know anyone who has this?’ There’s no food in the government stores. Everything has to be hustled by connection, by someone you know or farmers. And most of it can’t be had by legal means.”

Cars, buses and other transportation vehicles are also scarce, and many Cubans illegally convert bicycles into makeshift motorcycles called rikimbilis by attaching small motors. The bikes make a “deafening noise,” Oroza said, and riders seek alternative routes through cities to avoid traffic police. Large boxes welded to trucks become buses and the bottoms of old cars are sealed shut and refashioned as boats, used by defectors.

Parents also reinvent old plastic containers as toys like helicopters, cars and puppets.

“These are people that live with objects that are always disemboweled, the electronic guts exposed, while others keep things as if they were palimpsests, scraped clean of their prior functions,” Oroza said. “And both of these practices essentially lead to a dismantling of the object’s identity.”