Never mind that his latest restaurant, the over-the-top Bazaar Meat in Las Vegas, is a temple to suckling pig and foie gras.

José Andrés would like you to consider, for a moment, the vegetable.

Settled into a corner table of his Penn Quarter hot spot Jaleo, the small-plates king is animatedly spooning broccoli, carrots and snap peas into a surprisingly big bowl. In go rice, crunchy fried grains, a smoky sauce familiar to anyone who has eaten his Spanish cuisine. All the while, he is chomping on the vegetables with the zeal of a hungry dinner-party guest at the crudités spread.

This show — the carrots, the bowl, the talk about Chipotle founder Steve Ells — it’s all abstraction, the chef’s way of making a point about food: It does not have to be precious to be delicious.

Early next year, Andrés will join the constellation of famous chefs across the country who are launching fast-casual restaurants. Well aware of the landscape of fast-casuals around him in Washington, he’s staking out terrain that can be his alone: He will open a fast-food eatery that is vegetable-focused. And then, if all goes well, perhaps he will open a hundred more.

The first location of the cheekily named Beefsteak (after the tomato variety) will open on the campus of George Washington University, where Andrés created a course on food and serves as an adviser on food initiatives. He has been testing dishes with his staff for months.

“I’d prefer to have the army of great chefs we have in America opening multiple restaurants,” he says. “More than the McDonald’s and Burger Kings of the world opening restaurants.”

But hamburgers — frozen ones, flattened ones, even ones that are inexplicably dyed black — are an almost embarrassingly easy sell. There are legions who would declare themselves unable to stomach a broccoli floret.

Andrés protests. “A so-so vegetable, boil it in water, add some salt, it’s delicious,” he says. This is the gist of his Beefsteak pitch: “We don’t like to call it vegetarian. We want to call it tasty, fun, sexy, good-looking.”

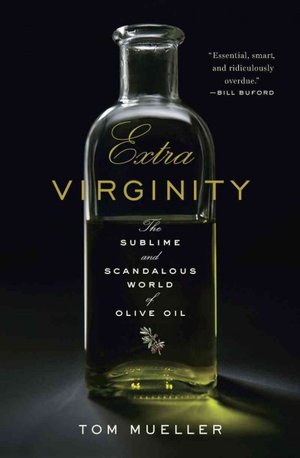

After a solid 10 years of pork-belly-everything and burgers so obscenely decked out (and priced) that they teeter on the pornographic, several chefs around the world have joined Andrés in singing the praises of salsify and beets, chard and sorrel. It’s less like they’re describing the next food movement, and more like they’ve undergone a full-on religious conversion. Alice Waters, perhaps the original vegetable evangelist, must be proud.

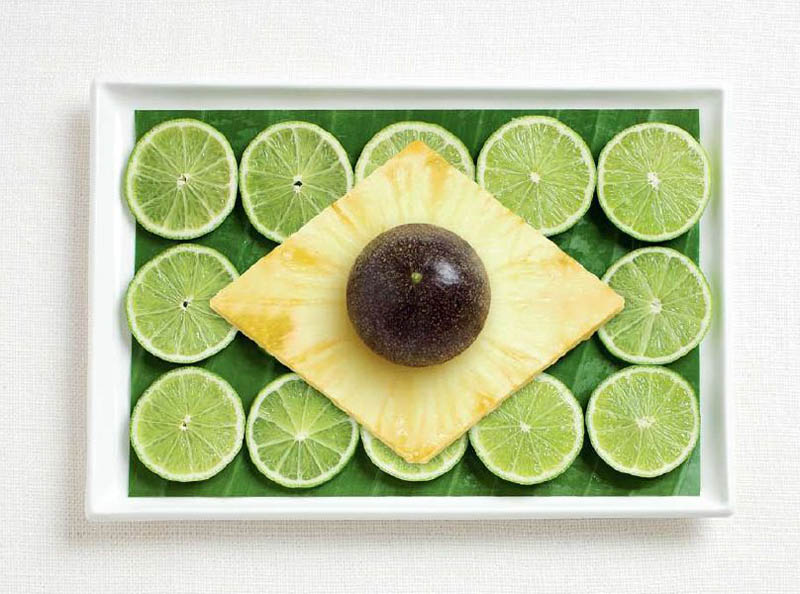

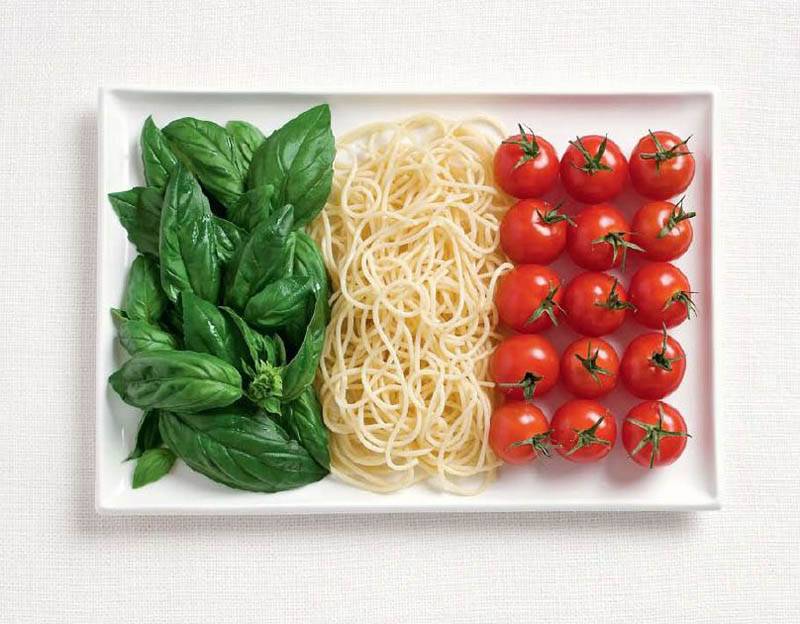

René Redzepi, the avant-gardist in the kitchen at Copenhagen’s Noma restaurant, is waxing poetic about the virtues of a limp old carrot. Mario Batali is embracing Meatless Mondays, and Eataly, his chain of mammoth Italian marketplaces-slash-mess halls, is ushering diners into the seats of its own vegetable-driven restaurant, where the chalkboard menu describes not specials but “today’s harvest.” In Los Angeles, Kogi food-truck baron Roy Choi has just delivered Commissary, a “vegetable-focused” (but, again, not vegetarian) restaurant. Choi wrote on his Instagram feed that he was “trying to make vegetable[s] relevant to a new generation by just making them fun.” Taking its soil-to-small-plate aesthetic to its most literal end, Commissary has diners eating in a greenhouse.

It’s not the first time Andrés has proselytized on the subject. In 2010, he memorably told “60 Minutes” correspondent Anderson Cooper that vegetables and fruits not only were the future, but also were “sexier than a piece of chicken.”

But in the case of most of these restaurants, including Beefsteak, to be vegetable-focused is not to break up with the chicken, frumpy though it might be. Rather, chefs such as Andrés imagine a world in which portions of old-fashioned proteins are negligible, perhaps even shoved off to the side like last decade’s broccoli. He suggests that Beefsteak will take a cue from the Chipotle model and emphasize diner empowerment. If a customer wants more cauliflower, he says, they will get it. But meat? “It’s a side dish,” he says.

“Vegetables are moving from the side of the plate to the center of the plate,” says chef Richard Landau of Philadelphia “vegetable restaurant” Vedge. Before opening the restaurant in 2011, he ran a place that was vocal about its vegan-ness; Vedge, like many of the nation’s vegetable-focused restaurants, carefully sidesteps that description. “We shun the word ‘vegan’ because it comes with a lot of preconceived notions,” Landau says. “They think there’s a bunch of stoned hippies back there listening to the Grateful Dead, stirring vegan chili and kale salads.”

This year, Landau, who says he spent his early days as a vegan chef apologizing for what he wasn’t serving, found himself a semifinalist for the James Beard Award for Best Chef: Mid-Atlantic, alongside such (meat-cooking) colleagues as Spike Gjerde of Baltimore’s Woodberry Kitchen and Cedric Maupillier of Mintwood Place in the District; his wife, Kate Jacoby, made the semifinalist list in the pastry category. This month, the couple will open a second, street-food-themed vegan restaurant, V Street, which, Landau says, they eventually would like to replicate in Washington.

This is not to say that vegetable-focused restaurants do not face a challenging learning curve with diners. Many of these chefs are making vegetables feel new with what we might call “the meat treatment.” Who can forget how quickly the nation changed its mind about Brussels sprouts (which we boiled, with nightmarish results, as recently as the 1990s) once we learned how glorious they could be when blackened, roasted or straight-up fried?

So, Vedge offers salt-baked kohlrabi with pho-spiced rice, while Table in Shaw serves cauliflower “steak” draped in hazelnut butter. At New York’s Dirt Candy, which had been so perennially booked up in its East Village digs that it is relocating to a space six times its current size, one of the most beloved dishes is a mousse that looks remarkably like foie gras. It is made from portobello mushrooms.

Dirt Candy’s owner and chef, Amanda Cohen, says that using techniques such as smoking and grilling is about recognizing “the flavors people like to eat and applying them to vegetables.”

“We’re not trying to have a mock meat. We’re not trying to mimic meat,” she says. “It’s its own cuisine, and it’s really coming into its own right now.”

Still, it remains difficult to convince diners that vegetables are much more than a salad or a side dish. Earlier generations saw vegetables as a kind of peasant food, a cheap way to fill a plate when meat was expensive. Eataly’s vegetable-focused Le Verdure “was a tough concept in the beginning because people thought you couldn’t make a meal out of vegetables,” says Alex Pilas, executive chef for Eataly USA. Even now, he says, the restaurant, which has been replicated at every Eataly location, does much of its business at lunch, when diners are in search of lighter meals.

And there is one more challenge: Many of the heartier vegetables that can add substance to a meal — the carrotlike salsify, rutabaga and sunchoke — are still relatively unfamiliar to diners, even those who frequent farmers markets and gourmet grocers.

To do the prep work for Le Verdure, and to prod along greens-averse customers, Eataly introduced the “vegetable butcher.” It’s a head-scratcher of a job title but based on a sound idea: To encourage shoppers to explore the produce aisles, the market offers to clean and slice and even advise customers on how to use watermelon radish, artichoke and even the mysterious sea bean.

Frederik De Pue, executive chef and owner of Table and Menu MBK, says restaurants can teach, too.

“People go to restaurants to discover things,” says De Pue. “They leave it up to the chef to make them discover new preparations. So that’s why, as chefs, we need to grab that, and use the celery root. People say, ‘I’ve never had that. Wow.’ ”

Andrés occasionally allows that the idea of a fast-casual vegetable restaurant is a wild one. But he says, “I believe this is needed.

“When we opened Jaleo, many people told me 20 years ago, ‘Tapas, it’s not going to make it. People in Washington like big portions, people are more conservative, people don’t like to share.’ ”

Sometimes, he says confidently, the public doesn’t know what it’s craving. It is the chef who points the way.