NPR

Making Moonshine At Home Is On The Rise. But It's Still Illegal

Within days after each season premiere and season finale of the Discovery Channel's reality show "," they come — a small but perceptible wave of people — to purchase suspiciously large amounts of corn, sugar and hardy strains of fermenting yeast at .

"We know what they're up to," says Chris Ellison, the manager of the Texas store.

That is, it's obvious they're planning to ferment the sugars from grain or fruit juice into alcohol, then distill the resulting midstrength beverage into high-alcohol hooch.

Making spirits at home with plans to drink it is federal law. Only with the right permits may a person make ethanol, either for use strictly as fuel, or as part of a commercial endeavor — like launching a craft spirits company, of which nationwide in recent years.

Yet more and more people seem to be making home moonshine, according to sources.

"The interest level is growing rapidly," says Gary Robinson, owner of , a supplier in Missouri. Robinson sells stills — which are perfectly legal to own — from roughly 3 gallons in capacity to about 13. He ships to all states, but the core regions of his business are the traditional Southeastern moonshine districts and the West Coast.

Mike Haney, owner of in Barlow, Ky., says his sales of ethanol stills have doubled every year for three years since he opened. "Just that someone buys a still doesn't mean they're out to break the law," Haney points out. "A lot of people are making fuel."

Haney also sells miniature oak barrels — the sort used for aging bourbon and brandy.

"But they might be aging wine in them, or just buying everclear from a supermarket and putting that in the barrel," he says. "Anyone can buy a barrel."

More HERE

4 out of 10 bottles that say Italian olive oil are not actually Italian olive oil

Listen HERE NPR Report on Olive Oil

Extra-virgin olive oil is a ubiquitous ingredient in Italian recipes, religious rituals and beauty products. But many of the bottles labeled "extra-virgin olive oil" on supermarket shelves have been adulterated and shouldn't be classified as extra-virgin, says New Yorker contributor Tom Mueller.

Mueller's new book, Extra Virginity: The Sublime and Scandalous World of Olive Oil, chronicles how resellers have added lower-priced, lower-grade oils and artificial coloring to extra-virgin olive oil, before passing the new adulterated substance along the supply chain. (One olive oil producer told Mueller that 50 percent of the olive oil sold in the United States is, in some ways, adulterated.)

The term "extra-virgin olive oil" means the olive oil has been made from crushed olives and is not refined in any way by chemical solvents or high heat.

"The legal definition simply says it has to pass certain chemical tests, and in a sensory way it has to taste and smell vaguely of fresh olives, because it's a fruit, and have no faults," he tells Fresh Air's Terry Gross. "But many of the extra-virgin olive oils on our shelves today in America don't clear [the legal definition]."

Extra-virgin olive oil wasn't created until stainless steel milling techniques were introduced in the 1960s and '70s. The technology allowed people to make much more refined olive oil.

"In the past, the technology that had been used had been used really by the Romans," says Mueller. "You grounded the olives with stone mills [and] you crushed them with presses."

The introduction of stainless steel milling techniques has allowed manufacturers to make more complex and flavorful extra-virgin olive oils, he says. But the process is also incredibly expensive — it costs a lot to properly store and mill extra-virgin olive oil. Mueller says that's why some people blend extra-virgin olive oil with lower-grade, lower-priced products.

"Naturally the honest people are getting terribly undercut," he says. "There's a huge unfair advantage in favor of the bad stuff. At the same time, consumers are being defrauded of the health and culinary benefits of great olive oil."

Bad or rancid olive oil loses the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of olive oil, says Mueller. "What [good olive oil] gets you from a health perspective is a cocktail of 200+ highly beneficial ingredients that explain why olive oil has been the heart of the Mediterranean diet," he says. "Bad olives have free radicals and impurities, and then you've lost that wonderful cocktail ... that you get from fresh fruit, from real extra-virgin olive oil."

On why 4 out of 10 bottles that say Italian olive oil are not actually Italian olive oil

"A lot of those oils have been packed in Italy or have been transited through Italy just long enough to get the Italian flag on them. That's not, strictly speaking, illegal — but I find it a legal fraud, if you will."

On extra light olive oil

"Extra light is just as caloric as any other oil — 120 calories per tablespoon, but the average person looking at it might say, 'Oh, well, I've heard olive oil is a fat, so I will try extra light olive oil.' ... It's highly, highly refined. It has almost no flavor and no color. And it is, in fact, extra-light in the technical sense of being clear."

Should Farmers Give John Deere And Monsanto Their Data?

Starting this year, farmers across the Midwest can sign up for a service that lets big agribusiness collect data from their farms, minute by minute, as they plant and harvest their crops.

and are offering competing versions of this service. Both are promising to mine that data for tips that will put more money in farmers' pockets.

But a leading farm organization, the American Farm Bureau Federation, is telling farmers to be cautious. These services, it says, could threaten farmers' privacy and give the big companies too much power.

The data in question come from detailed maps of farmers' fields.

Jonathan Quinn, who grows corn, soybeans and wheat on a large farm in northeast Maryland, pulls out a thick binder, opens it up on his kitchen table, and shows me an example. The rectangular outline of one field is covered with multicolored curved shapes, like a weather map showing areas of different temperatures.

The dark green areas, Quinn explains, are areas that produced higher yields. Light green and red areas produced less. "And this gray area, that's just zero yield," he says.

The amount of variation is astonishing. It happens because soil types vary, even within a single field. So does moisture.

Quinn pulls out the machine that collects the data for this map. It's a superaccurate GPS receiver — an oversize version of the kind you'd have in your car. At harvest time, it goes along in the combine, recording how much grain comes from every spot.

Later, at planting time, the receiver controls the planting machinery, placing seeds closer together where the soil is more fertile, or switching seed varieties to match conditions in different parts of the field.

Essentially, the planter is following a pre-programmed "prescription" for each part of the field. "It's all done on software," Quinn explains. "It's loaded onto a thumb drive; you stick the thumb drive into this [GPS display], and when you drive across the field, it automatically knows where it is because of the GPS."

Until now, all this information about his planting and harvest stayed in Quinn's hands.

But this year, he's taking the next technological step, participating in an experimental version of the data-sharing system that Monsanto is rolling out commercially in the Midwest.

Data will be transmitted directly from his tractor or combine into what computer people call "the cloud," where it will land on Monsanto's computer servers. "They're going to be able to see everything this [GPS] monitor does. So they're going to be able to look at my field all the time. They'll be able to look at my information, and they're going to just watch that field," Quinn says.

Monsanto thinks it can help farmers come up with the perfect prescription of seeds for their soil and weather because the company will have more data than any one farmer can collect or analyze. It will have more detailed soil maps and information from many other fields with similar soil conditions.

Eventually, it will have field-by-field weather predictions from a high-tech venture called the Climate Corp., which Monsanto bought last year for $1 billion. (The New Yorker an interesting profile of the Climate Corp. last November.)

"I've had people ask me, 'Why should Monsanto have all your information?' " Quinn says. "My theory is, if they have my information, and they're out there working with me, I'm hoping that they're going to bring me a better product. And them having my information doesn't bother me."

John Deere, the big farm machinery company, is offering something similar in collaboration with other .

Both companies are promoting this as a better version of what farmers do already. But the American Farm Bureau Federation is its members: Be careful. This is different.

Mary Kay Thatcher, the farm bureau's senior director for congressional relations, says farmers should understand that when data move into the cloud, they can go anywhere.

For instance: Your local seed salesman might get the data, and he may also be a farmer — and thus your competitor, bidding against you for land that you both want to rent. "All of a sudden he's got a whole lot of information about your capabilities," Thatcher says.

Or consider this: Companies that are collecting these data may be able to see how much grain is being harvested, minute by minute, from tens of thousands of fields. That's valuable information, Thatcher says. "They could actually manipulate the market with it. They only have to know the information about what is actually happening with harvest minutes before somebody else knows it. I'm not saying they will," says Thatcher. "Just a concern."

More HERE Via NPR

Someone needs to sample this Mooooooo

Cow-d it really be? Have our ears herd this correctly? (Sorry, I can't help myself.)

Patrick Stewart — ahem, Sir Patrick Stewart — mooed up a storm on the podcast , impersonating cows from various regions. You might even say Stewart was code-switching.

Click HERE to Listen Via NPR

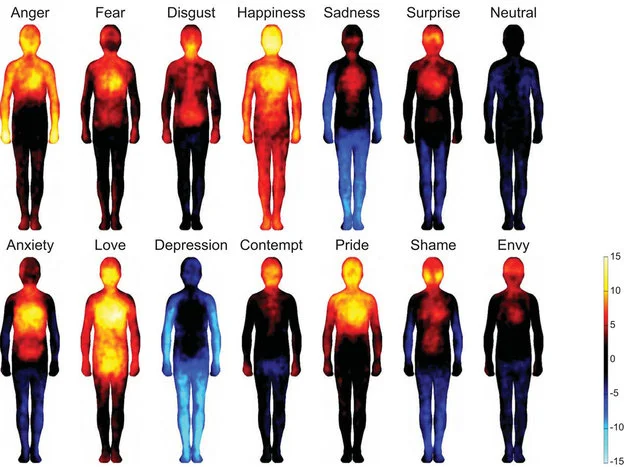

Mapping Emotions On The Body

Close your eyes and imagine the last time you fell in love. Maybe you were walking next to your sweetheart in a park or staring into each other's eyes over a latte.

Where did you feel the love? Perhaps you got "butterflies in your stomach" or you're heart raced with excitement.

When a team of scientists in Finland asked people to map out where they felt different emotions on their bodies, it found that the results were surprisingly consistent, even across cultures.

People reported that happiness and love sparked activity across nearly the entire body, while depression had the opposite effect: It dampened feelings in the arms, legs and head. Danger and fear triggered strong sensations in the chest area, the volunteers said. And anger was one of the few emotions that activated the arms.

The scientists hope that these body emoticons may one day help psychologists diagnose or treat mood disorders.

"Our emotional system in the brain sends signals to the body so we can deal with our situation," says , a psychologist at Aalto University who lead the study.

"Say you see a snake and you feel fear," Nummenmaa says. "Your nervous system increases oxygen to your muscles and raises your heart rate so you can deal with the threat. It's an automated system. We don't have to think about it."

That idea has been known for centuries. But scientists still don't agree on whether these bodily changes are distinct for each emotion and whether this pattern serves as a way for the mind to consciously identify emotions.

More here VIA NPR

Hair Dryer Cooking: From S'mores To Crispy Duck

This past year, we've introduced you to some wacky cooking methods. We've made an entire lunch in a Coffee Maker and even poached salmon and pears in the dishwasher.

But a few weeks ago, we stumbled upon a crazy culinary appliance that may be the most legitimate of them all: the hair dryer.

Now, before you think we've fallen off the kitchen stool from too much eggnog, check out the science and history behind the idea.

Hazen's classic recipe for roast duck contains this unusual twist: Dunk the duck in boiling water and then thoroughly go over it with a hair dryer, Hazen writes in Essentials of Classic Italian Cooking .

The result, she says, is duck skin that's "succulent" and "deliciously crisp" but not oily.

We'll explore exactly how the blow dryer helps crisp up poultry skin in a moment. But first, a bit of background — and some fun with chocolate.

The technique dates back to 1978, and it was pioneered by culinary guru , whom you might call the patron saint of Italian cooking in America.

The food scientists over at America's Test Kitchen three reasons to keep a hair dryer in the pantry:

1- relighting charcoals on the grill

2- putting a glossy sheen on cake frosting and

3- softening up a bar of chocolate to make it easier to shave off slivers.

Many of us don't have the time to give our cake frosting a professional blowout, but softening up chocolate struck a chord and made us immediately think of one thing: blow dryer s'mores!

Most hair dryers produce air that's about 200 degrees Fahrenheit when the nozzle is about 2 inches from a surface. That's the perfect temperature for melting chocolate (or butter) without burning it.

Read More Here Via SALT

India's Supreme Court Restores Ban On Gay Sex

India's Supreme Court on Wednesday that decriminalized homosexual acts, in a decision that is being called a major setback to gay rights in the country.

At issue was an 1861 British colonial-era law that forbids "intercourse against the order of nature." Prosecutions under Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code are rare, but are often used by police to harass gays and lesbians.

The Delhi High Court in 2009 ruled that the law violated the fundamental rights guaranteed by India's Constitution. But that decision was by Hindu, Muslim and Christian organizations, who welcomed the decision.

On Wednesday, the Supreme Court ruled that only Parliament can change the law. The decision was criticized by gay rights groups and their supporters.

"We see this as a betrayal of the very people the court is meant to defend and protect," said Arvind Narayan, one of the lawyers representing a consortium of gay rights groups. "In our understanding, the Supreme Court has always sided with those who have no rights."

Via NPR

In Meat We Trust: An Unexpected History of Carnivore America

We Got The Meat Industry We Asked For

The meat on your dinner table probably didn't come from a happy little cow that lived a wondrous life out on rolling green hills. It probably also wasn't produced by a robot animal killer hired by an evil cabal of monocle-wearing industrialists.

Truth is, the meat industry is complicated, and it's impossible to understand without a whole lot of context. That's where Maureen Ogle comes in. She's a historian and the author of In Meat We Trust: An Unexpected History of Carnivore America.

Ogle's book examines the pipeline that meat takes today from field to table by trying to understand its roots. She starts all the way back in Colonial America, when settlers found so much available land that they were able to raise livestock they could never have afforded in Europe. Meat, Ogle writes, became a status symbol in early America.

Much has been made of the ugly details of the modern meat industry, from Upton Sinclair's The Jungle to Michael Pollan's Omnivore's Dilemma to various exposes and . The industry's roots, though, stretch back more than a century, when Americans left their farms for the big cities, leaving a vast urban population with a cash income and a hankering for meat.

"As more people moved to cities, the gap between the amount of livestock and meat that could be produced constantly lagged the demand on the part of consumers," .

More here Via NPR

The Secret's Out: Obama Acknowledges Existence Of Area 51

At one time, Area 51 was one of the most famous military installations in the world — a place widely talked about, yet so secret that the U.S. government refused to confirm its existence.

That's why President Obama's reference to the southern Nevada base Sunday raised eyebrows. It marked the first time a U.S. commander-in-chief has publicly acknowledged the facility that fueled countless conspiracy theories.

Obama used the annual Kennedy Center Honors ceremony to crack a joke at the expense of actress Shirley MacLaine, one of the five award recipients, who has claimed to have seen UFOs on several occasions.

"Now, when you first become president, one of the questions that people ask you is 'what's really going on in Area 51?'" Obama said. "When I wanted to know, I'd call Shirley MacLaine. I think I just became the first president to ever publicly mention Area 51. How's that, Shirley?"

Conspiracy theorists have been obsessed with Area 51 for decades, claming — among other things — the government is holding aliens and crashed UFOs there.

The 1996 blockbuster movie "" cemented that notion in popular culture by depicting it as a highly secure repository for extraterrestrial beings and alien spacecraft.

A year earlier, President Bill Clinton had added to the mystery surrounding the facility by issuing declaring the site exempt from environmental disclosure laws following a lawsuit. Yet the document never actually referred to Area 51 — rather, it specified "the Air Force's operating location near Groom Lake, Nevada."

It wasn't until that the Central Intelligence Agency confirmed the existence of Area 51, officially known as the Nevada Test and Training Range and Groom Lake.

The newly released documents said the site served as a testing ground for aerial surveillance programs, such as the U-2 spy plane first used during the Cold War.

No mention of aliens or flying saucers, though.

Story here via NPR

What Separates A Healthy And Unhealthy Diet? Just $1.50 Per Day

If you want to eat a more healthful diet, you're going to have to shell out more cash, right? (After all, Whole Foods didn't get the nickname "Whole Paycheck" for nothing.)

But until recently, that widely held bit of conventional wisdom hadn't really been assessed in a rigorous, systematic way, says , a cardiologist and epidemiologist at the Harvard School of Public Health.

So he and his colleagues decided to pore over 27 studies from 10 different developed countries that looked at the retail prices of food grouped by healthfulness. Across these countries, it turns out, the cost difference between eating a healthful and unhealthful diet was pretty much the same: about $1.50 per day. And that price gap held true when they focused their research just on U.S. food prices, the researchers found in their of these studies.

"I think $1.50 a day is probably much less than some people expected," Mozaffarian tells The Salt, "but it's also a real barrier for some low-income families," for whom it would translate to about an extra $550 a year.

Still, from a policy perspective, he argues, $1.50 a day is chump change. "That's the cost of a cup of coffee," he says. "It's trivial compared to the cost of heart disease or diabetes, which is hundreds of billions of dollars" — both in terms of health care costs and lost productivity.

Read more here VIA NPR

Between Pigs And Anchovies: Where Humans Rank On The Food Chain

When it comes to making food yummy and pleasurable, humans clearly outshine their fellow animals on Earth. After all, you don't see rabbits caramelizing carrots or polar bears slow-roasting seal.

But in terms of the global food chain, Homo sapiens are definitely not the head honchos.

Instead, we sit somewhere between pigs and anchovies, scientists recently. That puts us right in the middle of the chain, with polar bears and orca whales occupying the highest positiohummn.

For the first time, ecologists have calculated exactly where humans rank on the food chain and how it's been changing over the past 50 years.

One trend is clear: Humans are becoming more carnivorous.

On average, people around the world get about 80 percent of their daily calories from fruits, vegetables and grains. The other 20 percent comes from meat, poultry and fish, scientists at the French Research Institute for Exploitation of the Sea in found.

"We are closer to herbivore than carnivore," the study's lead author, Sylvain Bonhommeau, Nature. "It changes the preconception of being top predator."

Read more here

Via NPR